gastro.ops

Gastronomy

Travel

Curiosity

Humanity

Stories

Food

Interviews

About me

FOLLOW ME:

MY ARTICLES:

THIS IS WHY YOU NO LONGER SHOP AT THE MARKET

For some strange reason, despite my parents have always taughtme the importance of proper nutrition, not just for our health but also for the planet and society, I had never gone grocery shopping at a market.

Don’t get me wrong: I’ve always shopped at the little organic store in my town, ready to sell a kidney and accept whatever nature had to offer based on the season.

Because of this, my lack of experience with markets didn’t bother me too much, until I visited Porta Palazzo Market in Turin.

It’s absurd that a generation like ours, Gen Z, so attentive to environmental issues and climate change, doesn’t shop at markets. Instead, markets are crowded with elderly women, armed with floral shopping trolleys, ready to push you into others just to grab the last cauliflower.

I started wondering why this is and decided to look for answers from the source closest to me: myself.

I must admit, the first excuse that came to mind was laziness, the lack of an adventurous spirit, and the convenience of having a supermarket just around the corner.

I felt ashamed, but at the same time, I sensed I was approaching a much deeper and more complex realization. I believe our society, so used to immediacy, to giving something no more than fifteen seconds of attention, and to endless choices, sees markets as a waste of time and, above all, as a limitation.

Markets offer only what the principle of seasonality allows, forcing us to change our plans, to adapt, and to invent new dishes.

They require us to take time to stroll, examine, ask questions, and listen.

Going to the market means challenging your habits, stepping out of your comfort zone for what?

For our health, for protecting the environment, and for promoting a short supply chain food system that empowers and respects farmers. The unpleasant smell of certain stalls can be tolerated, but the indifference that drives unconscious choices cannot.

HOW (NOT) TO WRITE A BORING CHRISTMAS ARTICLE

The idea for this article comes from my attempt to decide what to write about Christmas. In fact, every respectable gastronomy page rolls out tasty recipes easy to make in five minutes for the lunches during the holidays that need to feed hundreds relatives, original gift ideas like homemade candied fruit or jars filled with ingredients for specific recipes.

But what always makes me smile the most are the recipes for reusing leftover panettone or pandoro published even before the Christmas season begins.

Facing all of this, realizing that any idea I might come up with will never be entirely unique or original because someone else has already thought of it, I decided to write an article straight from the heart, without overthinking it about Christmas and a few truly unique gifts.

Indeed, one of the most meaningful gifts is surely to use the money you would spend on a potential present to provide a hot meal to the homeless in your city, to fund gifts for children and families in need, or to make a donation to a nonprofit organization.

It may sound like the typical hypocritical article trying to remind everyone of the true meaning of Christmas in an extremely consumerist and capitalistic society, but that’s where you’d be wrong: I’m not here to moralize. After all, when my sister told me at fifteen that instead of giving me a gift, she would have used that money to buy something for a needy family, I didn’t take it very well.

My intention is simply to offer a reflection from the perspective of someone privileged, someone who says every year they don’t want anything for Christmas but inevitably ends up wanting something and gets it without even asking.

Surely, none of us can bear the weight of an unfair and unbalanced world on their shoulders, but each of us can use a small part of their good fortune to bring a fragment of Christmas joy to those who cannot obtain it themselves.

What does this have to do with gastronomy? Probably not much, you might think but here’s where I’ll prove you wrong again.

Who could possibly think of Christmas without associating it with moments spent around the table with loved ones? No one.

Food, even in this case, can be a vehicle for love, justice, and generosity. Offering a hot meal is something anyone can do; it’s a gesture of humanity that shouldn’t be limited to the holidays but we all have to start somewhere.

HOW TO: FIND INCLUSIVE RESTAURANTS

As a person with specific dietary needs and a student off-site, I have often had absurd conversations on the phone to make it clear that parmesan is gluten-free and vegan does not mean without flour, in a desperate attempt to book a table.

For this reason I feel the need to share some strategies that I use when I go out to eat:

1. The first step, that I find extremely useful, is to look up the place on Tripadvisor and go see the section "special diets" that explains if the restaurant can meet certain needs (as in the case of gluten-free, vegetarian and vegan).

I google the official website of the restaurant to checl the menu. Marking allergens is a very positive, if not sufficient, sign of carefulness.

At this point, I call the restaurant asking for as much information as possible: for example, I always ask first if they have gluten-free pasta, a must have for me.

Having said that, even if they seem trivial things, they are often underestimated and make the experience extremely negative. Inclusion is a value that extends too little to food and meeting everyone’s needs.

An appeal to the friends of intolerant or allergic people is to avoid thinking in a selfish way, because often those who have to assert their needs already feel so embarrassed and do not need to feel even worse.

I hope that in the future more and more restaurateurs realize that besides the ethical and moral issue, which unfortunately matters little, there is a good economic gain because even one member of the group can make a reservation to be cancelled.

REIS: THE ROOTS TO WHICH WE NEED TO RETURN TO

I had the privilege of dining twice at “Reis – Cibo Libero di Montagna,” a restaurant tucked away in the remote and magical hamlet of “Chiot Martin” in the Valmala Valley.

The story of its owner, Juri Chiotti, is truly remarkable: a chef who pursued perfection and achieved it by obtaining a Michelin star, only to suddenly change his life with the vision of creating a new kind of cuisine, one that brings him genuine happiness.

Leaving behind the toxic world of Michelin-starred kitchens, Juri has crafted a reality built on the union of humans and nature, grounded in respect and care.

I like to think that every detail and element of the restaurant reflects a way of life, a deliberate stance that can even be considered political.

The idea of unconventional, slow cooking based on the principles of “good, clean, and fair” is a true innovation. With his garden and animals, Juri offers a cuisine that is authentic and wholesome in every sense. His approach is a quiet yet powerful fight against an unsustainable system that destroys the environment, the culture of food, and the health of all living beings.

At “Reis”, a name that means “Roots, the old times, during which humans adapted to what nature provided while respecting its cycles, is not just a memory but a living reality.

BETWEEN PHILOSOPHY AND FOOD - A BOOK NOT TO BE MISSED

When I visit a bookstore, besides making a beeline for the mystery section, I attempt a tentative approach toward the gastronomy shelf, only to be consistently disappointed: it's all keto cookbooks, pastry manuals, and guides on how to use an air fryer.

No offense to the air fryer, but gastronomy is so much more, and I even think it's impossible to confine it to a single shelf.

I’ll prove my point by referencing a very special book to me: “The Philosophers in the Kitchen: A Critique of Dietary Reason” by Michel Onfray.

This was my first reading about the world of food in the broadest sense of the term.

This book vividly illustrates the connections between the thoughts of famous philosophers and their dietary preferences, all revolving around one key question: would the philosophers we all know have made it into our philosophy books if they hadn’t listened to their stomachs?

Probably not, and the genius of this writing is right here, in the ability of the author to unveil the philosophical value of food that can be called the instrument through which our body changes and keeps alive.

The corporeal dimension, often overlooked by many philosophers as a symbol of human weakness and ephemeral pleasure, and opposed to the intellectual dimension, which aspires to serenity, knowledge and, in some cases, to the truth, it is instead fundamental in the formulation of a philosophical theory. We are made of flesh and this guides our actions, our opinions and beliefs.

What we eat, and especially what we don't eat, reveals a great deal about us and what we believe in.

I would describe the reading of this book as a game, an amusing journey between the giant lobsters that chase Sartre and the raw octopus that will mark the end of Diogenes' life.

CHRISTIAN DIOR AND HIS PASSION FOR THE FRENCH CUISINE

Published in 1972 and now available in a free digital version, the recipe book “La cuisine couse-main” tells not only about the passion of the French designer Christian Dior for the gastronomy and cuisine of his country, but also above all, the strong connection that binds food to the world of fashion.

With carefully crafted graphics, this collection of dishes ranges from the chervil soup, through the omelette soufflé, to the recipe for crepes and pear ice cream.

A special feature is the attention to certain ingredients such as various types of salad that are described in their distinctive flavour.

In the preface, friend and chef Raymon Thulier talks about Christian Dior's ability to find beauty not only in fabrics, colors and accessories, but also in the ingredients, harmony and balance of a good dish.

He liked to compare his work with that of the chef because "the ingredients we use when cooking are as noble as the materials used in high fashion".

His quest for semplicity and elegance was readily reflected in his food preferences: the recipes of the book are not elaborate or complex, but satisfying, able to satiate not only the stomach but also the spirit.

Now, food is an instrument, it is pure art in the hands of chefs who can be defined as stylists of taste able to create an unforgettable experience. So, is it surprising that you can pay for a dinner in a michelin star restaurant as much as for a designer bag?

THE SANREMO FESTIVAL AND FOOD - WHEN TWO WORLDS COLLIDE

The Sanremo Festival has put the life of all Italians on pause, ready to judge, listen and comment.

Ever since I became passionate about gastronomy, I have always wondered what possible connections might exist between the world of food and the one of music.

If a note, together with words, is the tool through which a musician tells stories, expresses thoughts and shares fears, food becomes a powerful means to communicate one's identity and culture. Moreover, both create communities, bringing people together and fostering a sense of belonging.

And what better occasion than the Festival of the Italian song to explore this complexity?

Already in the 1969 edition, Riccardo del Turco, with "what did you put in the coffee?", merged the two worlds.

"What did you put in the coffee I drank with you? There is something different about me now", sings del Turco about the moment he fell in love with a moment through the metaphor of coffee. In fact, this food refers to the conviviality, the moment of a relaxing pause that brings together families, colleagues and friends.

The intimacy and vulnerability that the singer feels in front of the woman he loves are contained in a cup.Luci Dalla also uses the lunch as a social metaphor with "PIazza Grande".

Dalla tells the story of a homeless man, between invisibility and sacrifice, and sings: " There are no Saints who pay for my lunch on the benches in Piazza Grande". The lunch is an emblem of sharing, union and affection, and here it is used to fully express the loneliness that grips the poor man.

Finally, Brunori Sas in the "Tree of the walnuts", in this edition of the program, touches complex themes related to paternity, family and growing old.

The leaves of the tree represent these steps in a delicate way: "The leaves on the walnut tree have grown fast and in your eyes of mother now shines a small flame".

In recent years, it has been a trend for competing singers to open temporary bars, kiosks or ice cream shops where they can serve food and meet fans.

So, food has made its way not only through the streets of Sanremo, but also onto the Ariston stage, strongly reaffirming its communicative power.

BALI: LEMBONGAN ISLAND BEYOND LUXURY RESORTS

As we sat by the sea, enjoying our lunch wrapped in a banana leaf, consisting of rice, chicken, sambal sauce, and seaweed salad, I realized that this story was worth telling.

We are on the small island of Nusa Lembongan, where, beyond the magnificent beaches and luxurious resorts, lies a lesser-known reality: that of the red seaweed farmers.

In a land unsuitable for agriculture and surrounded by particularly salty waters, the local community began this activity in 1984. Seaweed farming allowed the population to revitalize the economy and prevent a mass exodus due to scarce resources.

Today, Indonesia is the second-largest producer of red seaweed in the world, mainly for the food and cosmetics industries, thanks to carrageenan, which is used as a stabilizer and gelling agent. However, seaweed farming is far from easy, as it is influenced by various factors, primarily climate, sun exposure, and, consequently, climate change.

Another decisive factor is tourism. From 2016 to 2018, Bali’s growing popularity as a tourist destination led younger generations to abandon agriculture in favor of working in hotels and, more generally, in the hospitality sector.

For young people, the prospect of a difficult and poorly paid job is not appealing. The devaluation of the product and competition from Jamaica, which manages to produce at lower costs, have also put this industry under significant pressure.

However, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic forced everyone to stay home, pushing the Lembongan community to return to what could be considered its origins in order to survive. At that moment, the government decided to support seaweed production by providing tools such as nets and wood and covering the costs of planting. Additionally, since 2006, the government has committed to publishing national seaweed prices to ensure that producers are well-informed.

The government has also worked to establish connections between banks and farmers, enabling them to access financial aid under the condition that they form groups of at least 12 people. Currently, the Nusa Lembongan seaweed farming community consists of 30 members.

Local NGOs play a crucial role in organizing labor efficiently and supporting seaweed and cacao production, two industries that function only through strong community networks.

Farmers classify seaweed based on its color: if it is green (20 days of growth), it is replanted because it is not yet mature. If it turns yellow or white (45 days of growth), it is ready for drying.

The production process consists of several steps:

First, the seaweed is cleaned, tied to five-meter-long ropes, and attached to wooden stakes about 20 cm apart. The stakes are then placed 30 cm below the surface of the open sea.

For harvesting, the seaweed is pulled out of the water and sorted by size.

Seaweed does not need roots to grow, as it absorbs all necessary nutrients from the sea. Once brought ashore, the mature seaweed is dried in the sun, a process whose duration varies depending on weather conditions.

Farmers follow the lunar calendar for cultivation. In particular, the new moon and full moon are crucial moments, especially for harvesting, which takes place at night.

These communities are a perfect example of sustainable production, working with nature rather than against it and fostering strong social connections. However, the economic challenges make it difficult to sustain this labor-intensive craft, which requires knowledge, skill, and effort.

This article aims to highlight the stories I have been told and contribute to spreading awareness. In fact, we were strongly encouraged to share what we learned about seaweed production, as it is a way to help farmers gain recognition and visibility.

Digital diaspora and female empowerment: a new step in the gastronomic communication

Since the late 1990s, the Muslim community has been exploiting the opportunities offered by the web 2.0 for a number of purposes, including reconnecting and redefining themselves, but not only.

Social media has enabled Muslim women to acquire a space to fight the prejudices that relegate them to the margins of society.

In fact, there are several Muslim women who wear the hijab that share culinary content on platforms such as Instagram, Youtube or TikTok. Through their culinary performances, these influencers not only try to represent their religious identity and socio-cultural heritage, but also create social ties, using food as a bridge between the country of origin and the host society.

In fact, food is woven into a network of symbols, imaginaries and beliefs thus constituting a perfect vehicle for expression. In addition, studies from the Anglo-Saxon world have shown that nutrition confers autonomy and reduces gender power relations and stereotypical categorizations by increasing women’s empowerment. Cooking is an act of love not only towards others, but also towards oneself because it constitutes a self-representation.

Nella maggior parte dei casi, i contenuti pubblicati raccontano la vita quotidiana delle donne musulmane velate che vivono in una realtà in cui l’Islam è minoritario, come nell’Europa Occidentale. In questo contesto, la rappresentazione dell’hijab assume un significato importante poiché spesso, all’interno del paese ospitante, viene percepito come un ostacolo alla piena integrazione della comunità musulmana. Ciò innesca un processo di minorizzazione per cui l’individuo minoritario viene assegnato sempre al suo collettivo di riferimento, al suo gruppo etnico o razziale che si presume lo rappresenti. All’interno dei loro canali, le hijab influencer instaurano una comunicazione dialogica con il loro pubblico che assume la forma di “cultura transnazionale di auto aiuto” ,come la definisce Sonali Pahwa. Vi è una necessità di reinterpretare una ricetta familiare in un rituale di memoria nostalgica tipico dei contesti diasporici. Dunque, i social diventano uno spazio attraverso il quale le donne musulmane sfidano gli stereotipi associati alla loro fede presentando un immagine lontana dalla sottomissione.

In addition, social media contributes to the process of democratization of halal "conscious that is becoming accessible and attractive to an ever-wider audience. At the same time, the future of social communication of one’s food heritage presents many challenges related to exclusion, sustainability, security and veracity of information. The network structure, minimal access control and increased awareness of an outgroupare key to creating a dynamic of inter-group discrimination. Precisely for this reason, it is important to educate the young generations to a correct use of the Internet with the aim of creating safe places of sharing in respect of the various religious, cultural and food identities. In this latter case, in addition to the difficulty of relating to other communities, an issue arises regarding the future communication of food in relation to topics that are extremely important nowadays, such as sustainability and ethics. In fact, to fully understand halal "conscious, it is necessary to go beyond the simple legality of products and apply the concept of Tayyib that means "good" and "healthy". This means paying more attention to the origin of the ingredients, farming practices, working conditions of producers and the environmental impact of the entire production process.

In this sense, the global market must meet an increasing demand for a"conscious consapevole” che soddisfi nuovi criteri di qualità complessi e multidimensionali. Per il raggiungimento di tale obiettivo, è necessario affrontare le sfide legate alla sensibilizzazione dei consumatori, alla collaborazione tra i vari attori della filiera produttiva e alla trasparenza delle etichette e delle informazioni.

Il sale di Kusamba: tra tradizione ed estinzione

Percorrendo le spiagge vulcaniche di Kusamba, nel sud di Bali, è possibile imbattersi nei produttori di sale, custodi di questa antica pratica. La particolarità di questa attività risiede non solo nel prodotto finale, denso di nutrienti e dal caratteristico gusto umami grazie alla composizione dell’acqua della zona, ma anche nel processo produttivo, estremamente affascinante da osservare.

Si inizia con la raccolta dell’acqua di mare attraverso uno strumento rudimentale e con la sua evaporazione all’interno di quadrati di sabbia nera con l’obiettivo di ottenere una soluzione pura. Successivamente, quest’ultima viene fatta cristallizzare in recipienti scavati in un tronco della palma da cocco per circa 5 giorni. I cristalli formatesi spontaneamente vengono separati dal resto della soluzione attraverso utensili appositi e fatti sgocciolare per rimuovere ulteriormente il liquido.

Al termine del processo, si ottengono circa 10-12 tonnellate di sale al mese durante la stagione secca.

Mantenere viva questa tradizione è essenziale per la preservazione del patrimonio gastronomico di Bali e per la tutela di intere comunità che sono vissute grazie a questo mestiere. Oggi, l’industrializzazione erode inesorabilmente la cultura di questi luoghi con il contributo del governo che favorisce il sale iodato considerandolo più salutare.

Tutto ciò ha portato all’inserimento di queste realtà all’interno del progetto dell’ “Arca del Gusto” di Slow Food, nato per la tutela e la promozione di prodotti e pratiche su piccola scala che rischiano di scomparire.

È responsabilità non solo delle istituzioni, ma anche dei singoli consumatori dare voce a queste comunità estremamente potenti, ma invisibili attraverso lì acquisto diretto del loro prodotto o la diffusione delle loro storie.

Labour Exploitation System: Not All Workers Can Celebrate Today

In occasione della Festa dei Lavoratori, è necessario ricordare tutte le persone vittime del caporalato, una forma di sfruttamento lavorativo che si insinua con particolare prepotenza nel settore agricolo e che riguarda sia italiani che stranieri. Questo fenomeno interessa tutta la penisola italiana sin dagli anni ’70 ed è condannato dall’articolo 20 della legge 83/1970 sulle “Norme in materia di collocamento e accertamento dei lavori agricoli”. La figura centrale su cui si fonda l’intero sistema è il caporale, che funge da intermediario tra il datore di lavoro e la manodopera. Si occupa della selezione degli aspiranti lavoratori e del loro trasporto dal punto di ritrovo al campo e viceversa, e della negoziazione delle mansioni e del compenso ottenendo in cambio una parte dello stipendio dei braccianti.

Il tutto ovviamente nella logica di un’economia in nero in cui non vengono rispettate le leggi sul lavoro e i diritti dei lavoratori. La necessità di manodopera stagionale che comporta un rapporto lavorativo breve e la possibilità di sfruttare stranieri spesso irregolari rendono l’agricoltura la realtà in cui si registrano più illeciti per caporalato. In particolare, viene reclutata la componente più debole della forza lavoro che in passato era formata dalle donne, ma che, a partire dagli anni ’80, interessa sempre di più gli immigrati provenienti sia dall’Unione Europea sia dal Medio Oriente e Africa subsahariana .

This has created a violent and deeply unjust environment, driven on the one hand by the desire to control a workforce that has no family or economic ties to the area and is therefore able to move where wages are higher, and on the other by the precarious conditions these individuals face, which force them to accept any kind of job.

One of the most recent reported cases involves 12 Asian-origin workers in the Asti countryside, who were humiliated, abused, and forced to buy their own tools, earning just a few hundred euros a month and living in dilapidated housing. This is the result of new, hidden forms of the labour exploitation system, known as “landless cooperatives”, particularly widespread in Piedmont. These are associations that offer agricultural services and labor without owning land. They often operate from fake addresses and exploit legal loopholes to evade inspections.

The labour exploitation system has spread across many other countries, taking on various forms. In her work “On the Move for Food: Three Women Behind the Tomato’s Journey”, Deborah Brandt explores what it means to be a woman in the world of agriculture, telling the stories of Tomasa, Marissa, and Irena. She describes the FARMS (Foreign Agricultural Resource Management Service), which exploit laborers who work long hours for low pay, without overtime compensation, access to social benefits, or the right to unionize.

In un giorno come questo, che celebra tutte le lotte per i diritti dei lavoratori, è importante continuare a battersi per coloro che vivono nell’incertezza e nella paura, e che non possono assaporare la conquista della legalità.

Subak Uma Lambing: Where Tradition Feeds the Future

In Indonesia, on the island of Bali, the Subak is much more than a traditional irrigation system for rice fields. It is, in fact, a perfect example of social and spiritual cooperation aimed at creating an alternative agricultural system that respects the natural environment and local religious beliefs.

A partire dal IX secolo, il Subak supporta la produzione di riso, principale componente della dieta balinese, e consente una gestione sostenibile ed equa delle risorse idriche che coinvolge tutti gli agricoltori del villaggio. Questi ultimi si riuniscono regolarmente per discutere e decidere di numerose questioni quali le tempistiche da rispettare per l’irrigazione e la quantità di acqua da utilizzare. Inoltre, è presente un capo, il Pekaseh, eletto dalla comunità secondo le peculiari regole dei singoli Subak. Egli si occupa di coordinare le operazioni di irrigazione, eleggere il Pujari, sacerdote, per celebrare i rituali ai templi dell’area e di sanzionare i membri.

The system is deeply tied to the Hindu religion and is based on the philosophy of Tri Hita Karana, an expression that can be translated as "three causes of well-being." According to this principle, prosperity arises from the relationship between humans and God, harmony among people within the community, and balance between humans and nature. Water is considered a sacred gift to be managed collectively, and irrigation becomes a symbolic offering to the gods of water and fertility in hopes of a bountiful harvest.

Today, the legacy of the Subak lives on in modern and dynamic forms such as Subak Uma Lambing, a cooperative of 250 farmers located in Sibang Kaja.

The history of Balinese agriculture has led to the creation of this project, which aims to recover native rice varieties, use natural fertilizers, and adopt sustainable farming practices.

During the 1970s and 1980s, farmers were encouraged through subsidies to grow hybrid seeds and use chemical fertilizers and pesticides with the promise of better yields. However, this apparent prosperity came at the cost of serious environmental and social consequences. The Subak Uma Lambing initiative seeks to remedy these issues through multiple approaches.

In addition to returning to traditional farming methods, the cooperative has also become an eco-tourism destination in response to the damaging trend of converting farmland into mass tourism infrastructures.

This initiative is the result of collaboration between the local Subak leader, the Green School, the Astungkara Way Foundation, and the Renature Foundation. Tourists are invited to immerse themselves in authentic Balinese culture through activities such as harvesting and sun-drying rice, sharing daily life with farmers, and working the land.

On the legislative side, this alternative development model is supported by local regulations and national laws such as Law No. 22/2019. Furthermore, the Nawacita government program launched by President Joko Widodo promotes sustainable agriculture through the goal of establishing 1,000 Organic Villages.

While there is no recent data confirming the achievement of this goal, significant progress has been observed in various areas of Indonesia, such as the Sanggau district. This transformation has not only strengthened local economies and improved soil quality, but has also fostered female leadership. At the same time, consumer choices are evolving toward more sustainable and high-quality food.

Clifford Geertz, one of the fathers of contemporary anthropology, described the Subak as an intricate social world that shapes, and is shaped by, the environment. The Uma Lambing project represents a traditional and dynamic system that seeks to preserve a lifestyle rooted in Balinese culture, that of the farmer, through sustainable practices that honor the land and the natural resources regarded as sacred gifts from the divine.

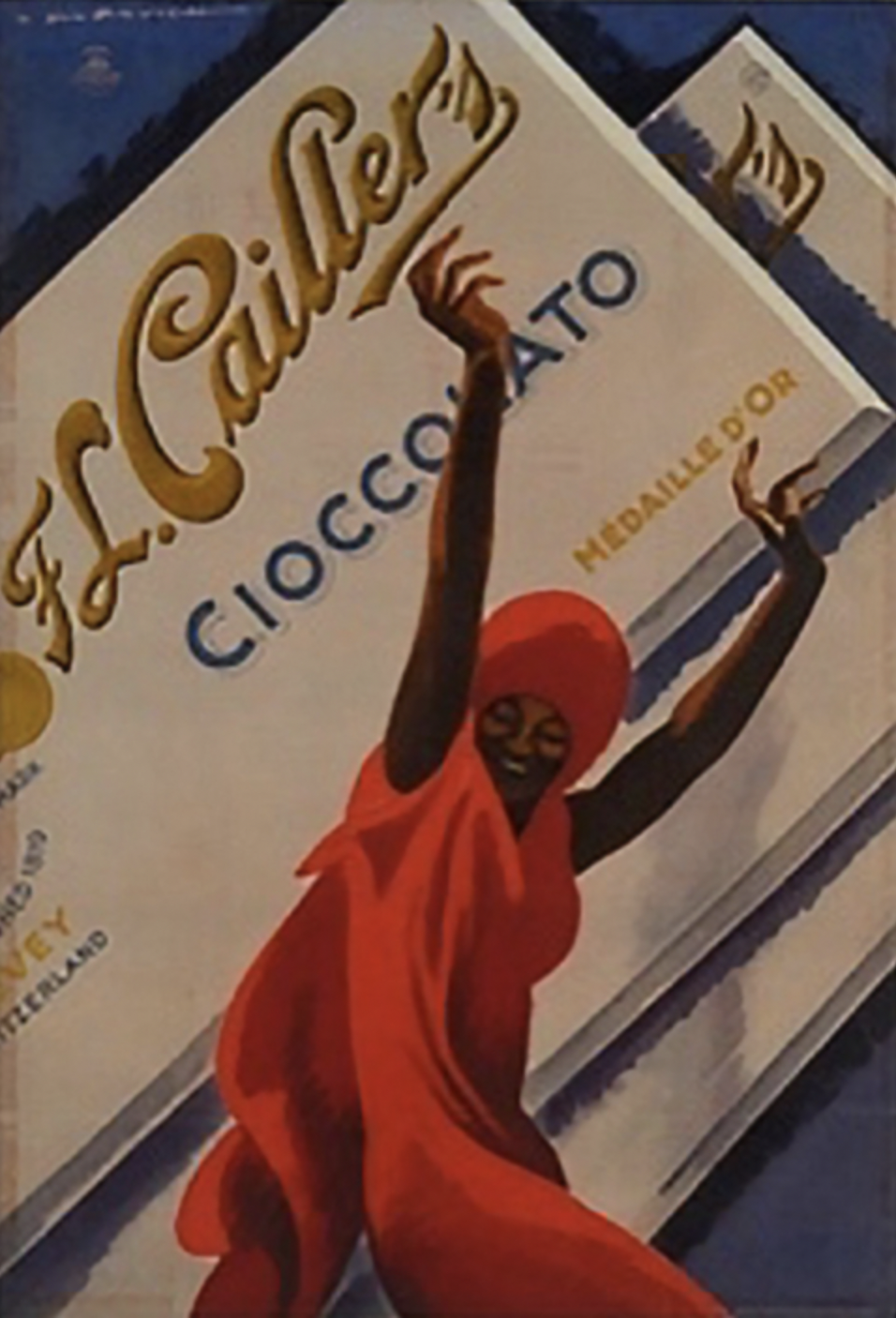

Colonialism, Racism, and Chocolate: A Story Worth Knowing

Food is not only a source of sustenance for humans but also a symbol of power, culture, belonging, and a tool of political propaganda. Sometimes, it becomes an emblem of exploitation and social injustice, as in the case of cocoa, a globally consumed product that holds a history of pain and oppression. This product, widely distributed around the world, was for many years seen as a status symbol, representing a luxurious lifestyle. It was an exclusive food reserved only for certain social classes but also a cornerstone of the colonial economy, a system based on the violation of human rights and the use of African Indigenous peoples as labor.

This racial discrimination was also reflected in the advertising strategies used to represent chocolate, which became a symbol of exoticism and domination. As Professor Simone Cinotto writes in his book Gastro Fascism and Empire: “"The language of advertising took on a different, more ambitious and diversified tone toward ‘colonial food’" Art directors and graphic designers worked on these products to create a connection between colonial food and the metaphorical consumption of the bodies of colonized populations.

Advertising was not only meant to attract consumers, but also to promote the expansionist projects that several nations, such as Britain, Spain, France, and Italy, were carrying out in Africa. Italy in particular contributed significantly to the spread of a racist narrative linked to chocolate, which during the Fascist era was advertised with clear references to the superiority of the white man. As Professor Gabriele Proglio writes in his article Food Advertising and Italian Colonial Propaganda: "Fascist colonial propaganda was aimed at emphasizing the role of the fatherland (Patria, in Italian, the land of the fathers) and had a civilizing mission: these themes were disseminated in the public sphere both through state propaganda and private narratives using various media (radio, newspapers, Istituto Luce, cinema, etc.)."

Simple design and the use of racist stereotypes were the key elements of colonial advertising, which aimed to highlight the contrast between the colonizers, seen as bringers of progress and innovation, and the invaded people, portrayed as primitive, backward, and in need of the white man's guidance. As Emma Robertson explains in her book Chocolate, Women and Empire: A Social and Cultural History:

"The use of Black people in advertising has a long history. As Jan Pieterse shows, products made available through slave labor, such as coffee and cocoa, often used, and many still use, images of Black people to elevate their luxury status" (Robertson, 2010).

Over time, advertising evolved and the colonial theme was forgotten. However, controversial ads continue to circulate such as the Magnum ice cream ad, where a Black woman is shown with a cracked shoulder, resembling the breaking of the chocolate shell of the iconic dessert. In this case, the sexualization of the naked female body is evident, but more importantly, it shows a racialized metaphor connecting the woman’s dark skin to chocolate.

As Monica Di Sisto wrote in the newspaper Il Manifesto: "Advertising doesn’t see us as citizens, but only considers us if we are consumers. The market only cares about those who can buy. As if there were no real limits to what nature produces—and to what each of us can actually eat."